Breaking the Shell

Tiffin could crack an egg with one hand. I didn’t know it was possible to crack and egg with one hand. I stood on a stepstool, the top of my head still reaching only to his bottom rib, and watched my mother’s famed cousin mix pancake batter for breakfast. He tapped the delicate shell of each egg on the edge of a steel mixing bowl, opened it with long fingers shaped into a soft fist, and threw the empty husk into the kitchen sink in one easy motion. The whole process with one hand. I could not believe it.

For the first time in my life, they were here. I came downstairs, old enough to be aware of my little-girl bedhead but not yet willing or able to resolve it on my own, to see my mother sitting at her kitchen island, coffee in hand, soaking in their presence. Towering at 6’5” and 6’7”, the brothers filled our spacious kitchen. They bobbed around each other, their large and lanky bodies used to negotiating tight spaces. They bantered and laughed while they flipped and sizzled, mixed and poured out breakfast for their family and mine.

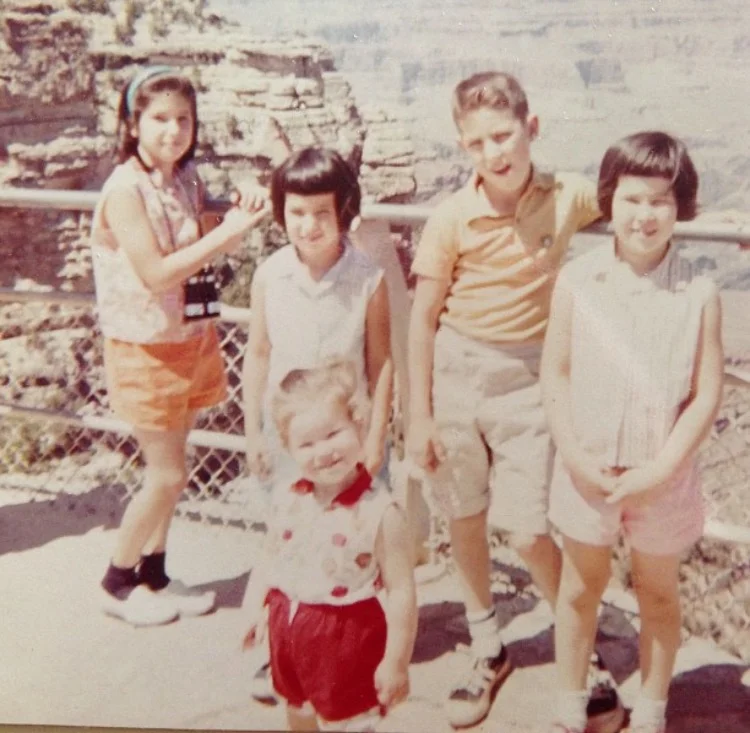

My mother idolized her cousins. Their brood of four brothers and one long suffering sister mirrored my mother’s family of four girls and one boy, adding symmetry. To her, they were summers exploring the woods around her aunt’s cabin in Oak Creek Canyon and visiting their double wide trailer in Colorado, where the kids would pile two or three in a bed to fit all fifteen bodies of both families combined. They were the naive independence of youth and some much-needed liberation from the rigorous religious restrictions of her father’s house.

To me, they were a link to a family I struggled to understand, a window through which I viewed my mother as a whole person, with a past and a life beyond my brother and me. I knew a few stories of these brothers, the hi-jinks they would get up to in those crowded, free roaming summers. Otherwise, mother was tight-lipped about her history. I tried to piece it together from snippets of memory she would occasionally let sneak out: Her first day of school, when her brother stood at the chain link fence separating their schoolyards, protecting her during her first recess through gaps in the wire. The outfit she would wear out of the house to meet up with her high school boyfriend — and the outfit she hid underneath it with a mix of fear and rebellious zeal. The small Southern turns of phrase her mother carried from coal mining country to California, a very few of which I still heard in my own mother’s drawn pronunciation of words like “hund-erd” and “wawrsh”. Mostly, though, my mother's family was just trips to Disney world and cool older cousins that I saw once or twice a year. They were intimidating in their closeness, their loud voices, and their look-alike faces blurring together at large family gatherings in a way my brother and I, familiar with family dynamics of a smaller, quieter kind, could not yet decipher. We had only each other to contend with.

Reid and Tiffin, however, occupied a mythic plane. Like Indiana Jones or Huckleberry Finn, these two oversized characters traipsed through my mother’s previous life in my imagination, herself a character I could never really know: far removed from the woman who picked me up from soccer practice and stumbled into dinner late, still wearing scrubs from work, most nights. But this morning, I could see in her eyes the shine of her former self, the fierce young woman wrestling her way into independence, sheltered by her family, and so eager to see what else the world would bring. I started to see her in her history and fallibility, and heroes of her own. There they were, standing in our kitchen, serving pancakes.